Listen to Michael Mann, a climatolgist at Penn State University who talked about the science behind global warming and rising sea levels.

Any honest assessment of the science is going to recognize that there are things we understand pretty darn well and things that we sort of know. But there are things that are uncertain and there are things we just have no idea about whatsoever. (Nate Silver, The Signal and the Noise, 2012, p. 409).

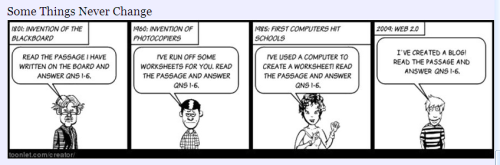

Ah, if only federal and state policymakers, researchers, and reform-minded educators would see the “science” of school reform in K-12 and higher education in similar terms. “Science” is in quote marks because there is no reliable, much less valid, theory of school reform that can predict events or improvements in schools and classrooms.

Still, for K-12 children and youth there are “things we understand pretty darn well.”

*We understand that socioeconomic status of children’s families has a major influence on students’ academic achievement.

*We understand that a knowledgeable and skilled teacher is the most important in-school factor in student learning.

*We understand the wide variability in student interests, abilities, and motivation.

*We understand that children and youth develop at different speeds as they move through the age-graded school.

Readers can add other “things we understand pretty darn well.”

Then there are “things that we sort of know.” Such as some schools with largely low-income, minority enrollments out-perform not only similarly-situated schools but schools that serve families from middle- and upper-middle income schools.

Or that the more educational credentials graduates collect over time, chances are they will earn more in their lifetime than those who fail to finish school and college.

Or that curriculum standards can outline what students have to learn but the tests–and the rewards and penalties tied to those tests–measuring whether students have reached those standards have a powerful extensive influence on what teachers teach and what students learn.

And there are “things that are uncertain” in schooling children and youth. Consider that over the past quarter-century, the dominant goal for public schools has been college preparation. This is a political decision driven by fear of unskilled U.S. graduates unable to work in ever-changing companies which will fall behind in global competition. The primary way of insuring that administrators and teachers achieve that goal has been regulatory structures of federal and state accountability accompanied by high-stakes incentives and penalties. This also is a political decision for the same reason given above.

Uncertainty has arisen because some parents, researchers, teachers, and policymakers have contested both the goal and structures. Why? Because so many high school graduates have failed to meet college admission standards. Because so many who do go to college drop out after a year or two. Because costs of going to college climb annually. Because K-12 curriculum standards and accountability rules have narrowed what is taught to that which is tested.

Thus, conflicts over the goal and regulatory accountability have created many doubts about the wisdom of these reforms especially in light of mounting evidence that overall academic achievement or the achievement gap between whites and minorities remains pretty much stuck where it was when the reforms were enacted.

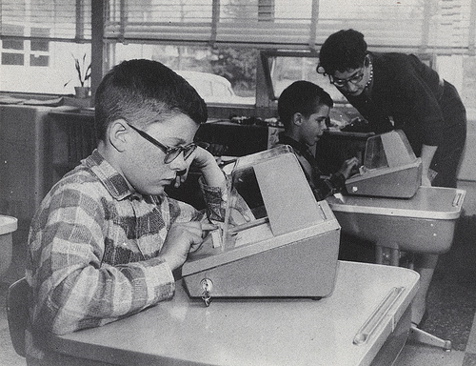

And there is uncertainty over the value-added to student learning from new technologies ranging from children using 1:1 iPads or laptops to students learning online. Uncertainty increases ambivalence among policymakers, researchers, practitioners, and parents over whether deploying expensive hardware, software, and professional development increases, has little effect, or even diminishes academic achievement.

Finally, “there are things we just have no idea about whatsoever.” Can anyone predict with any confidence the probability, for example, that when Common Core standards and their accompanying tests kick in by 2015, students academic achievement will rise, propel college ready students into higher education, have them graduate, and get jobs that will grow the U.S. economy? Can anyone predict with confidence, to cite another reform, what will occur as a consequence of evaluating teachers, on the basis of how well or poorly their students do on standardized tests?

Or whether or not MOOCs will “revolutionize” higher education.

No one can.

The fact is that few who style themselves as school and university reformers in positions of authority sort out publicly what they know from what they don’t know. Or say out loud their doubts about reform proposals under consideration or which have just been launched. Name me a top-level decision-maker who has publicly stated his or her qualms about the worth of a reform they championed. Instead, policymakers and pundits talk from their bully pulpits and deliver overconfident predictions often overstating what will happen and underestimating the difficulties and complexities of making changes.

Unlike Michael Mann, a scientist who publicly says what is known, unknown, and when uncertainty is present, reform-driven educators and non-educators, working with little theory and even less scientifically gathered evidence, bang the drum daily for transforming schools and higher education. They do so without telling recipients what they know, do not know, and what is uncertain in these innovations or revealing to any extent what are the political, social, and economic costs of putting the reform into practice. School reform is filled with ambiguity and guesswork. That is the untold story.