I had a conversation with a dear friend* a few years ago that has stayed with me. We had been talking about something I had written detailing my failures as a teacher with students I have had over the years. He had practiced Family Medicine for over a half-century in Pittsburgh and for years helped resident physicians in doing medical research and improving communication with their patients. He pointed out to me how similar teachers experiencing failures with students is to physicians erring in diagnoses or treatments (or both) of their patients.

I was surprised at his making the comparison and then began to think about the many books I have read about medicine and the art and science of clinical practice. In my library at home, I had two books with well-thumbed pages authored by doctors who, in the first dozen pages, detailed mistakes either they had made with patients or errors committed by other physicians on them or their families.

In one, Jerome Groopman, an oncologist, described what occurred with his 9-month old child after a series of doctor misdiagnoses that almost caused his son’s death. A surgeon, who was a friend of a friend, was called in at the last moment to fix an intestinal blockage and saved his son’s life.

In the other book, surgeon Atul Gawande described how he almost lost an Emergency Room patient who had crashed her car when he fumbled a tracheotomy only for the patient to be saved by another surgeon who successfully got the breathing tube inserted. Gawande also has a chapter on doctors’ errors. His point, documented by a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine (1991) and subsequent reports is that nearly all physicians err.

If nearly all doctors make mistakes, do they talk about them? Privately with people they trust, yes. In public, that is, with other doctors in academic hospitals, the answer is also yes. There is an institutional mechanism where hospital doctors meet weekly called Morbidity and Mortality Conferences (M & M for short) where, in Gawande’s words, doctors “gather behind closed doors to review the mistakes, untoward events, and deaths that occurred on their watch, determine responsibility, and figure out what to do differently (p. 58).” He describes an M & M (pp.58-64) at his hospital and concludes: “The M & M sees avoiding error as largely a matter of will–staying sufficiently informed and alert to anticipate the myriad ways that things can go wrong and then trying to head off each potential problem before it happens” (p. 62). Protected by law, physicians air their mistakes without fear of malpractice suits.

Nothing like that for teachers in U.S. schools. Sure, privately, teachers tell one another how they goofed with a student, misfired on a lesson, realized that they had provided the wrong information, or fumbled the teaching of a concept in a class. Of course, there are scattered, well-crafted professional learning communities in elementary and secondary schools where teachers feel it is OK to admit they make mistakes and not fear retaliation. In the vast majority of schools, however, no analogous M & M conferences exist (at least as far as I know).

Of course, there are substantial differences between doctors and teachers. For physicians, the consequences of their mistakes might be life-threatening, even lethal. Not so, in most instances, for teachers. But also consider other differences:

*Doctors see patients one-on-one; teachers teach groups of 20 to 35 students four to five hours a day.

*Most U.S. doctors get paid on a fee-for-service basis; nearly all full-time public school teachers are salaried.

*Evidenced-based practice of medicine in diagnosing and caring for patients is more fully developed and used by doctors than the science of teaching accessed by teachers.

While these differences are substantial in challenging comparisons, there are basic commonalities that bind teachers to physicians. First, both are helping professions that seek human improvement. Second, like practitioners in other sciences and crafts, both make mistakes. These commonalities make comparisons credible even with differences between the occupations.

Helping professions.

From teachers to psychotherapists to doctors to social workers to nurses, these professionals use their expertise to transform minds, develop skills, deepen insights, cope with feelings and mend bodily ills. In doing so, these helping professions share similar predicaments.

*Expertise is never enough. For surgeons, cutting out a tumor from the colon will not rid the body of cancer; successive treatments of chemotherapy are necessary and even then, the cancer may return.

Some high school teachers of science with advanced degrees in biology, chemistry, and physics believe that lessons should be inquiry driven and filled with hands-on experiences while other colleagues, also with advanced degrees, differ. They argue that naïve and uninformed students must absorb the basic principles of biology, chemistry, and physics through rigorous study before they do any “real world” work in class.

In one case, there is insufficient know-how to rid the body of different cancers and, in the other instance, highly knowledgeable teachers split over how students can best learn science. As important as expertise is to professionals dedicated to helping people, it falls short—and here is another shared predicament–not only for the reasons stated above but also because professionals seeking human improvement need their clients, patients, and students to engage in the actual work of learning and becoming knowledgeable, healthier people.

*Helping professionals are dependent upon their clients’ cooperation. Physician autonomy, anchored in expertise and clinical experience, to make decisions unencumbered by internal or external bureaucracies is both treasured and defended by the medical profession. Yet physicians depend upon patients for successful diagnoses and treatments. If expertise is never enough in the helping professions, patients not only constrain physician autonomy but also influence their effectiveness.

While doctors can affect a patient’s motivation, if that patient is emotionally depressed, is resistant to recommended treatments, or uncommitted to getting healthy by ignoring prescribed medications–the physician is stuck. Autonomy to make decisions for the welfare of the patient and ultimate health is irrelevant when patients cannot or do not enter into the process of healing.

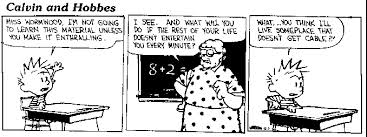

For K-12 teachers who face captive audiences among whom are some students unwilling to participate in lessons or who defy the teacher’s authority or are uncommitted to learning what the teacher is teaching, then teachers have to figure out what to do in the face of students’ passivity or active resistance.

So while doctors, nurses, and other medical staff have M & M conferences to correct mistakes, most teachers lack such collaborative and public ways of correcting mistakes (one exception might be in special education where various staff come together weekly or monthly to go over individual students’ progress).

Books and articles have been written often about how learning from failure can lead to success. Admitting error without fear of punishment is the essential condition for such learning to occur. There is no sin in being wrong or making mistakes, but in the practice of schooling children and youth today, one would never know that.

_______________________

* Dr. Joel Merenstein and I have been close friends since boyhood in Pittsburgh (PA). He passed away in 2019.