I have yet to meet anyone publicly opposed to increasing the number of three and four year olds going to preschool. Most parents, policymakers, and researchers broadcast the pluses of this early childhood experience and some call for universal prekindergarten as now exist in New York City, Oklahoma and other states and districts (for an exception, see Bruce Fuller’s Standardized Childhood).*

Sure, the reasons given range from the adult dividends that these four-year olds will accrue in high school and adulthood, reducing economic inequality, and giving working mothers and low-income families child care and job opportunities. While there are naysayers when it comes to these future outcomes, expanding high quality child care and education to young children is seldom questioned (see here and here).

Given there is near unanimity on the importance of pre-kindergarten, many states have mandated preschooling and many districts have incorporated these children into the system (and paid far higher salaries to credentialed teachers). Still only 40 percent of eligible pre-kindergartners have access to publically funded preschool. The rest are in private, for-profit settings and home care. Compare that to other nations.

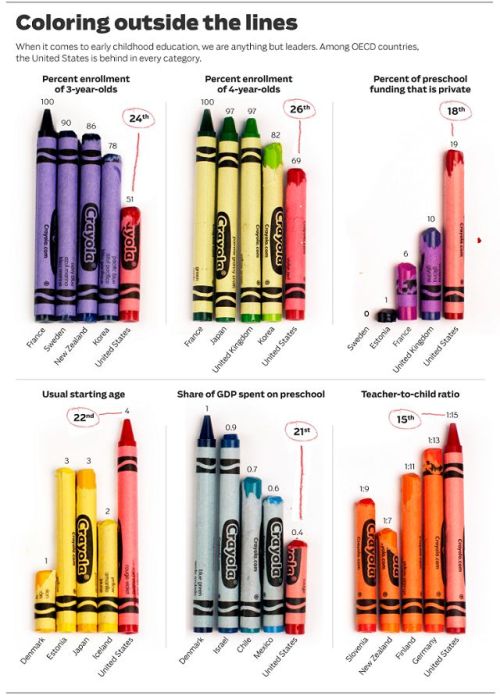

The OECD made up of 35 economically developed nations in Europe, North America, and Asia ranked access to government financed preschools in 2015. For three- and four year-olds, the U.S. came in toward the bottom of the distribution.

When U.S. students score in the middle or bottom of rankings of results on international tests, mainstream media pays close attention to where the nation ranks. Not so for such rankings as these.

Rhetorical support for preschools in U.S. is way ahead of actions in enrolling prekindergartners across the 50 states as it is on the credentials and salaries of teachers who daily educate their young charges both in public and private preschools.

Consider the core dilemma that few members of education policy elites want to talk about much less tackle: with near unanimity on the importance of preschool to individual children, their parents, and society, those who teach preschoolers outside of public schools (predominately female) are paid just above the poverty level.

The facts are worrisome:

* Average annual preschool teacher salary in 2016 was just below $29,000. Poverty level established by U.S. government for a family of four in 2017 is nearly $25,000.

*Preschool teachers in school districts who have teaching credentials earn as much as elementary teachers, $55,000 (2016)

So what the U.S. faces is near unanimity on the economic and social importance of preschool experiences with noticeable shortcomings on, first, providing equitable access to all three and four year-olds as a nation and among the states, and, second, paying a workforce that is (97 percent female of whom most are low-income women of color with a high school diploma ) just above the poverty level.

Obviously increased spending for expanded preschool and teacher salaries has been and is a major stumbling block. Yet historical trends in expanding access to tax-supported schooling in the U.S. and rising teacher salaries offer a splinter of hope to those who take the long-term view.

First, adding new populations to public schooling has occurred time and again. Recall that kindergartens were late-19th century middle-class women’s private efforts to educate five and six year olds before they entered elementary school. Those model kindergartens were slowly integrated into public schools beginning in the 1880s and by the 1950s had become K-12 age-graded schools (see here).

A similar pattern is occurring with preschools albeit in a more accelerated fashion. Publicly-funded prekindergarten classes have been authorized by many states and exist in scattered big cities across the nation (see here and here). How soon, I cannot say, but I do see pre-K becoming integrated into nearly all public schools across the U.S.

As for the huge disparity in salaries for non-credentialed preschool teachers and those preschool teachers who work in public school systems with licenses to teach, that, too, I believe will move, again slowly, to narrow the salary differential that now exists. Preschool teachers getting associate and bachelor degrees in early childhood education through a growing array of online and on-site universities will increase, again slowly since the cost of taking courses and earning credentials remain prohibitive to single and working mothers who are a major proportion of those who staff preschools.

So the long-term view I offer here is optimistic as to the dilemma I see facing preschools in the U.S. But the long-term means years, even a few decades which is of little comfort to those who earn near-poverty level salaries and have to choose between providing essentials for their families and finding money to finance their quest for a teaching credential.

The gap between rhetoric and action when it comes to preschooling in the U.S. remains large.

____________________________

*Rob Kunzman corrected me on my first sentence. He sent me a paper produced by the Home School Legal Defense Association that opposes federally funded preschool on the grounds that the research is far from definitive, the high cost of the program, and further erosion of parental rights (see here and here). Thanks, Rob.

“Working mothers who are a major proportion of those who staff preschools.” And that is likely to continue, along with regarding preschools as child care centers and little more, or if “more” then an academic bootcamp for entry into elementary school.

I worry most about the funding of preschools by social impact bonds, also known as pay-for-success contracts.These are financial products designed to produce a return on investment in the range of 6% to 75%. Cohorts of children are provided services, but the children are screened to rule out those with serious learning problems. Investors earn money if the “service providers” succeed in getting successive cohorts of students to meet targets, such as reading by grade three.

One of the screening measures in the Peabody Picture Test. Programs in Chicago and Utah are being financed in this way, along with some in Australia. Outside evaluators are hired to assess the success of the program. A representative from the investors may gain a seat on the board of the service provider (e.g., United Way) and also have the power to hire and fire at will to improve performance.

In other words, what is offered, by whom, and how well is judged by return on financial investment, profits made. I think this is not a great premise for a full-spectrum educational program for preschoolers, nor is the exclusion of children with disabilities. Indeed, the premise and marketing pitch is that children with mild learning problems will get an early intervention and thus save the school system big bucks by having lower enrollments in special education.

Laura, here again you got me to read further on “social impact bonds” to fund early childhood schooling, particularly about Utah’s initiative. I found the Brookings report (https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Impact-Bonds-for-ECDweb.pdf) to be helpful also. Paymrnt for results hooked to the Peabody test and other student outcomes is indeed there. Thanks.

Reblogged this on David R. Taylor-Thoughts on Education.

Thanks for re-blogging post on preschool, David.

Dear Dr. Cuban, Thank you for this blog entry and your highlighting of the important teacher-pay/credential issue. I am very interested in your perspective on the “chicken-n-egg” problem that we are experiencing in the early childhood profession. No credentials -> Low Pay; Low Pay -> No credentials. There are efforts in our field to raise credentials FIRST, in order to attract more pay (National Association for the Education of Young Children, “Power to the Profession” initiative). But I am concerned that 1) there may not be plausible theory/history in support that approach; 2) by raising credentials without making it accessible for low-income providers, we essentially segregate and exclude mostly low-income providers of color out of the “profession”. It will artificially raise the “pay” by simply having a more educated, whiter base. I’ve only looked briefly into the history of wage in nursing and teaching (two other professions once staffed by underpaid women). But the history is complex – from supply/demand factors (nurses) and unionization (teachers). Can you shed some light on plausible/implausible pathways that can increase wage without “pushing out” low-income staff?

Thank you.

Thank you for your comment Juniei Li. There is a history that may apply to preschool non-credentialed teachers. Whenever there have been shortages in, say, bilingual or special education teachers, states and districts have turned to aides with a high school diploma to give them both emergency certification and access to credentialing courses paid for by district and/or foundations. There are such shortages at present in preschools within public school systems.