Carson Rietveld invited me into her 9th grade World Studies class on September 16, 2016. She has been teaching for four years at Mountain View High School.* The class is furnished with four rows of desks facing the front whiteboard; the teacher’s desk is in the far corner. Music is playing as students enter the room. Student work, historical posters, and sayings dot the walls above the white boards (e.g., “I want to live in a society where people are judged by what they do for others).

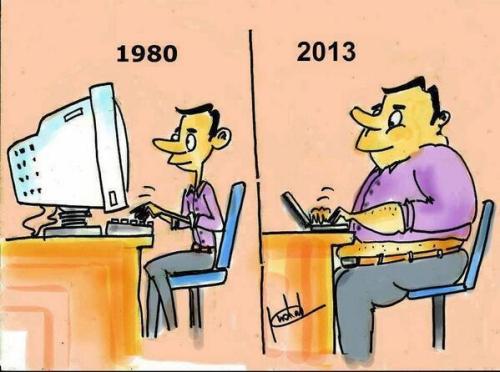

Rietveld, wearing a long flowered dress that reaches her ankles, welcomes the 14- and 15 year old students by name as they come in. Students put their backpacks on the floor near a side whiteboard and bring their tablet or laptop to their desk. The high school policy is Bring-Your-Own-Device (BYOD).** I ask a student why do all backpacks go on the floor and he tells me that students rooting through their backpacks during a lesson distracts both the student and teacher from what is being taught. Thus, the rule.

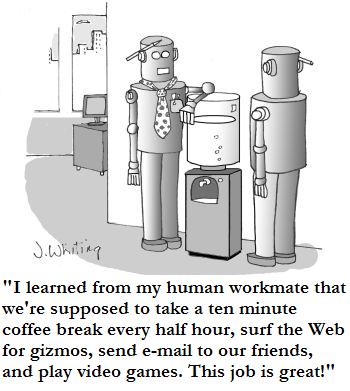

The 27 students sit at their desks, take out their devices, surf the Internet, and talk to one another. Bell rings to begin class. Music stops. School announcements come on the public address box in the room. Many students listen and some whisper to one another or continue looking at their device. After announcements end, Rietveld directs students’ attention to front whiteboard with a slide showing the agenda for “Happy Friday Fresh Friends.”

*Mindfulness exercise

*Partner presentation practice

*Roman Republic presentation

*Whole class discussion

EQ: what makes a good presentation?

EQ: how much influence did the average citizen have in the Roman Republic?

(EQ refers to Essential Question. See here)

Teacher goes over the agenda and asks students to close lids of their computers. They do. The first agenda item is a mindfulness exercise. A video comes on with a soft, soothing voice asking everyone to “ground themselves in the now.” The voice asks viewers to close their eyes—I look around the room and all students’ eyes are closed—and the soothing voice asks viewers to concentrate on relaxing their toes, ankles, legs then “shifting awareness” up through the entire torso to their head. Teacher participates with students. Rietveld tells me that she now has her students doing up to three minutes of the daily exercise.

Rietveld segues to next activity, listed as “Partner Presentation Practice” which will give students a chance to practice getting at the substance of the lesson, the relationship between the Roman Republic and democracy. Students will be making presentations and the teacher wants students to practice getting at the essential point they wish to make in their presentation and the argument (including evidence) that will support that essential point.

To get students to practice this task, Rietveld asks them to take two minutes to find a photo of the cutest cat or dog they can find on the Internet. Then write a paragraph why their photo is the cutest and afterwards turn to their partner and explain why—what features of the pet make it the cutest, etc.

After a few moments, she says ,“20 seconds left to finish.” Teacher has a stopwatch in her hand and uses it to announce time. Then she says press “submit” wherever you are in the paragraph so I can see what you have written (Rietveld uses Pear Deck and has access to each student’s work).

“Now present the animal to your partner, “ Rietveld says. “What kind of animal did you pick? Why did you pick this animal? Explain why you think it is the cutest.”

After two minutes, teacher asks the listening partner to present their “cutest” pet photo.

I look across the classroom and all pairs and trios appear involved in task.

After time is up, teacher asks each partner to write down “ a thoughtful idea they did well.”

“OK,” Rietveld says, “let’s go over your awesome thoughts—I see partners making eye contact and directing the other person back to photo. Give multiple reasons and focus on different features. Talk slowly.”

She then asks students to open up their computers and write down they could have done better. What mistake did partner make. I see nearly all students clicking away on their devices. But some are talking and seemingly off-task. Teacher says: “OK, guys, self-regulate, self-regulate. Don’t have photo of pet on screen; it will be distracting. Get rid of it,” she says.

After waiting a few minutes, Rietveld segues to next activity of small group work to give practice to students in presenting their answers to the “essential question”: Based on what you have read, “How democratic do you think was the Roman Republic.”

Students have been thinking about this question and have made posters with illustrations and text to state their answer to the question when they present to the entire class.

Rietveld directs students to get into small groups after designating the different roles that students will perform in the group they are in. Teacher points to one side of room and says that these students are “time-keepers”; another side are “facilitators”, in the middle are “resource managers”, and in the rear are “harmonizers”—specific roles that apparently students are familiar with. Then she directs that each member of a group will present their answer to the “essential question: “How democratic do you think was the Roman Republic.”

After presenting in their small group, each student will resume their role as the next student presents answer to question. Students rearrange themselves, move desks and chairs as they settle into their groups to present to one another their answer to the question:

Using the stopwatch, Rietveld announces how much time is left. After ending the task, she then asks students to critique presenter, that is, what one thing the presenter did well; what one thing that can be improved. Then she announces that the next student is to present. Students circulate their posters and present for another two minutes.

Looking around the class, I see all small groups engaged in listening to presenter and showing their posters. Teacher walks around listening to each group. One group looked off-task to her so Rietveld goes over and asks presenter—“What is one piece of evidence in your poster about Roman Republic being democratic?”

For the next six minutes presenters in the small groups shift from one student to another with the teacher announcing when the two minutes are up. In each instance, Rietveld asks group to go around their circle and tell the presenter one thing they did well and one thing they can improve upon.

After stop-watch alarm rings, the teacher brings the activity to a close. She asks students to close their computers and segues to the final task of the period, The Four Corners Discussion of a slide flashed onto the whiteboard: “The Roman Republic a True Democracy.”

She tells class that each student should consider whether they strongly agree, somewhat agree, strongly disagree or somewhat disagree with the statement and then “vote with your feet.” After waiting a few moments, Rietveld directs students to go to a corner of the room for strongly agree, another corner for those who strongly disagree, etc.

Teacher looks where students are. Most are either in one of two corners expressing disagreement or agreement with statement. Rietveld asks entire class, “why there is disagreement among you about statement. Some students in one corner call out and say that not everyone could vote—women and slaves; teacher pushes back and asks for evidence; student give example and teacher probes again. Then another student in an opposite corner gives evidence of democratic practices. Students around her nod their heads.

“Why don’t we totally agree,” teacher asks? A few students say there is evidence on both sides. Another student says that there is a lot of “subjectivity on what is a true democracy,” a peer adds that the conflict is over differing values that students have about democracy and which ones are most important.

Then the bell rings ending the period. Rietveld asks students to return desks to their original position. They do. She wishes them “a safe weekend.” Students go to pick up their backpacks lying on the floor near the wall and leave the room. World Studies is over for this class.

___________________________

* Part of the Mountain View-Los Altos High School District, Mountain View High School has just over 1800 students (2015) and its demography is mostly students of color (in percentages, Asian 26, Latino 21, African American 2, multiracial 2, and 47 white). The percentage of students eligible for free-and-reduced price lunches (the poverty indicator) is 18 percent. Eleven percent of students are learning disabled and just over 10 percent of students are English language learners.

Academically, 94 percent of the students graduate high school and nearly all enter higher education. The school offers 35 Honors and Advanced Placement (AP) courses across the curriculum. Of those students taking AP courses, 84 percent have gotten 3 or higher, the benchmark for getting college credit. The school earned the distinction of California Distinguished High School in 1994 and 2003. In 200 and 2013, MVHS received a full 6-year accreditation from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC). Newsweek ranks MVHS among the top 1% of high schools nationwide. The gap in achievement between minorities and white remains large, however, and has not shrunk in recent years. The per-pupil expenditure at the high school is just under $15,000 (2014). Statistics come from here and mvhs_sarc_15_16

**BYOD began two years ago in the District.