My memory of teaching over a half-century ago is filled with holes. In thinking back to the time when I began teaching at Glenville High School in Cleveland (OH) in 1956 as a 21 year-old novice, I can recall some events, some students, some teachers, but there is much I forgot. I do remember well, however, that the students were nearly all Negro—the words “black” and “African American” were not in general use then.

As for what I did daily in my five U.S. and world history classes that year and the next six that I taught there, only slivers of memory come to mind. And even those fragments are disconnected. I do have students’ reminiscences of lessons I taught, a few actual “study guides” that I prepared weekly for my U.S. history classes, student papers with my comments on them, occasional articles about one or more classes of mine in the student newspaper, and photos of me teaching in the annual yearbook. That’s it.

In assembling those shards of memory and documents from more than a half-century ago knowing what I know about teaching history to teenagers, I find it hard to sort out what I actually did in my classroom from what I would have liked to have done.

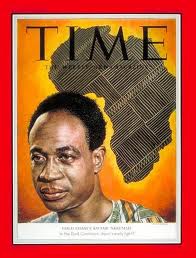

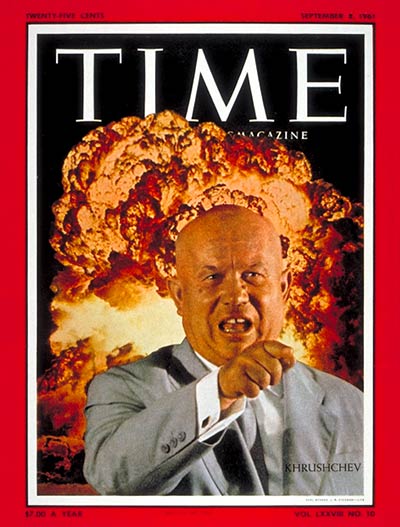

Consider current events in history courses. I do remember that I set aside Fridays to teach current events. Either in my first or second year of teaching, I began posting covers of Time magazine showing national leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union, Richard Nixon and Lyndon Johnson of the U.S., and Mao Tse Tung of the People’s Republic of China. These Time covers lined the ledge above blackboards—this is before green or white chalkboards–that ran along the front wall and one side of my classroom. I would change these colorful portraits and photos as leaders came and went in their countries.

In those 45-minute periods on Fridays, as I recall, I taught a teacher-directed lesson on a newspaper article or international event that I found connected to something I had taught recently in U.S. or world history such as a coup d’etat, the election of a President, a Cleveland event, or something that occurred at Glenville high school itself. Students could receive extra credit (I used a point system to grade students) for bringing in newspaper and magazine articles that they could connect to what we were studying the rest of the week. They would report on the article to the class—yes, they had to stand at the front of the class where my desk was located—summarize the article they described and then take questions from me and other students. I do recall that students in the late-1950s brought in and reported on articles about Little Rock (AR) where the state governor refused to protect nine Negro students into Central High School after a federal court had ordered school officials to admit those students.

On Monday through Thursday, I would teach lessons on the “golden age of Athens” or Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act followed on Friday by articles on the Montgomery (AL) bus boycott (1956) or on the Suez Canal crisis (1956). Sure, I recall making efforts, sometimes vainly, to tie together disparate topics on successive days but on Friday, chronological history went out of the window. How come?

At that time among social studies academics and teachers was the prevailing progressive belief that for history to be engaging and meaningful teachers had to connect the past to the present. Integrating the past with the present would help students see connections that they could not see in tramping through the textbook from the explorers discovering North America through the 13 colonies to the American Revolution to the Civil War to collapsing with fatigue around World War I. Although the word relevance was seldom used then, the idea of making past events real to students by locating contemporary connections prevailed. In theory, that is.

So as a novice teacher managing five classes a day of around 175 students, believing in that integration of the present to the past, I set aside one day a week to do just that. Other, more experienced teachers, might have connected past to present with examples in daily lessons rather than setting aside an entire period once weekly. I did not.

Did it work for me? Yes, because I would try to make links in choosing articles, Time covers, and discussions with each class. Doing so, stretched me intellectually. Did it work for students? I have no idea.

Fast-forward to 2013. While few social studies teachers will quarrel with the importance of linking the past to the present, the standards-based, accountability, and testing dominant in U.S. schooling now often prevents setting aside precious time as I did a half-century. While there are still calls (see here and here) for more current events taught in history courses, how much of that kind of integration occurs, I cannot say.

I did a small workshop for teachers during the professional development day last week on using QR codes for social studies teachers. One topic that was enthusiastically received was posting QR codes for the major online newsmagazines and news outlets. Posting these codes would make it easy for students to scan the code and quickly reach these media outlets. So I would say that, yes, teachers are taking the time to squeeze in current events as much as they can, and relevance is huge to them. It may not be to the depth we would like for lack of time and the pressure of testing, but making connections keeps history real.

Thanks, Sandy, for the information on QR codes for social studies teachers in Arlington.

Pingback: Recapturing How I Taught U.S. History a Half-ce...